Real knowledge is to know the extent of one's ignorance

Confucius said in 500BC “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance”.

Photo by Glen Noble on Unsplash

Photo by Glen Noble on Unsplash

This concept has come up in a few conversations recently.

As your experience and knowledge increases across a range of topics, you may not feel any more knowledgeable. Why might this be? It turns out there’s a simple explanation.

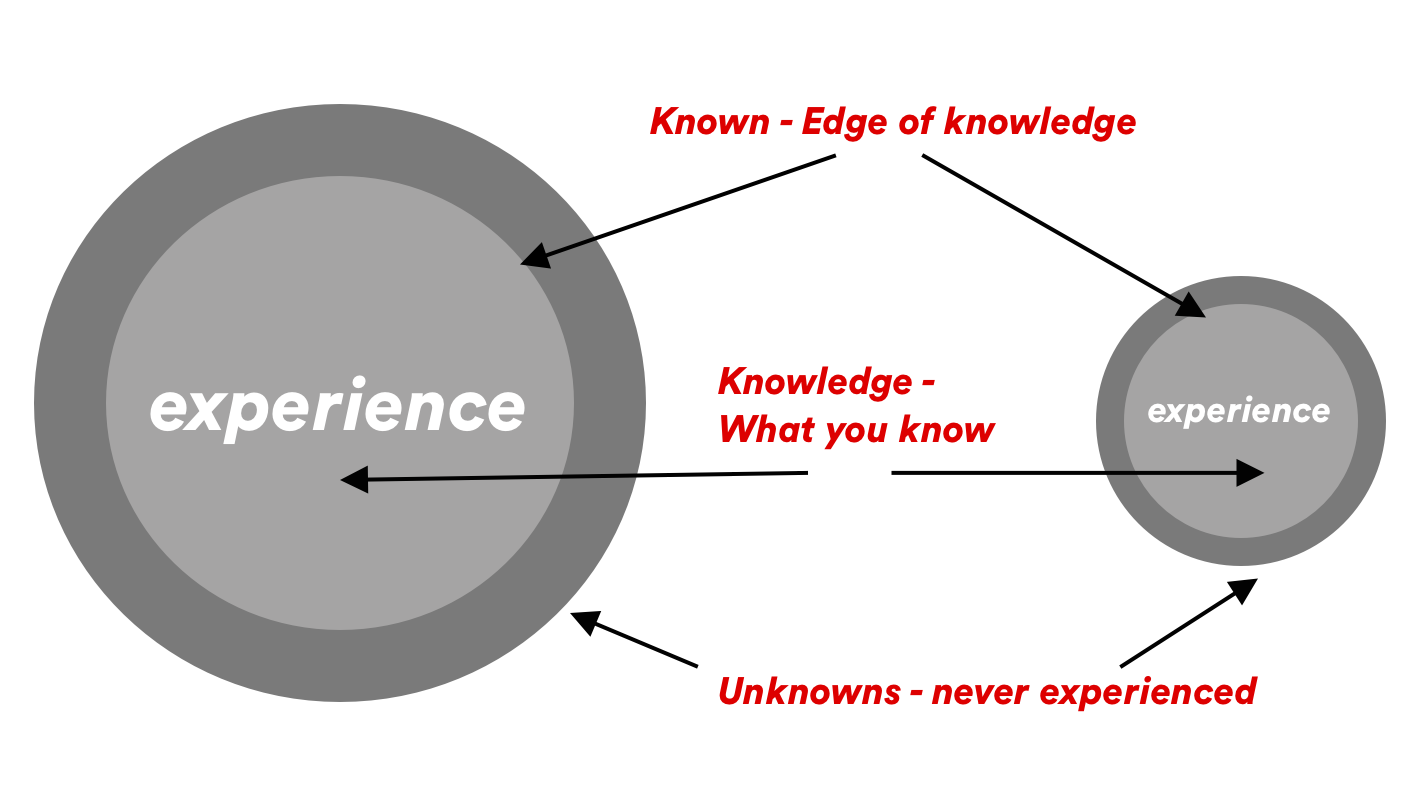

As your experience and knowledge expands, you encounter more topics and understand existing topics more deeply. Your circle of knowledge increases.

On the edge of this knowledge circle are the topics you may have encountered, but don’t know. As your knowledge and experience increases, you know more topics exist.

As your ‘knowns’ increase so do your ‘unknowns’. You know that you don’t know more :WINK:

Circle of knowledge

Circle of knowledge

Ok, so this model might explain it. How does this help, what can we do with this knowledge? And our newfound knowledge of our lack of knowledge!?

Imposter syndrome

Imposter syndrome is a psychological pattern where you may doubt your accomplishments and fear being exposed as a fraud. You may attribute your success to luck and discount both your achievements and ability.

With the above model, knowing what you don’t know plugs in here. Being more aware of this balance between knowledge & unknown can help you evaluate your true abilities and value your achievements.

Dunning-Kruger effect

In the opposite direction is the Dunning–Kruger effect. This is a cognitive bias where people mistakenly assess their cognitive ability as greater than it is. Related to the illusory superiority bias, a cognitive bias where people fail to recognise their lack of ability.

I’ve encountered this issue regularly. The junior who over confidently proposes a risky or inappropriate solution. The manager who’s very strong opinion on a topic is misguided. Or the loud person at a party explaining something incorrectly.

Unknown Unknowns

Rumsfeld said it nicely with this quote

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

When we understand the limits of our knowledge, we can make better decisions. Just identifying and recognising what we don’t know helps. We can then develop a plan to improve our knowledge, or at a minimum flag them as a risk.

Four Stages of Knowledge

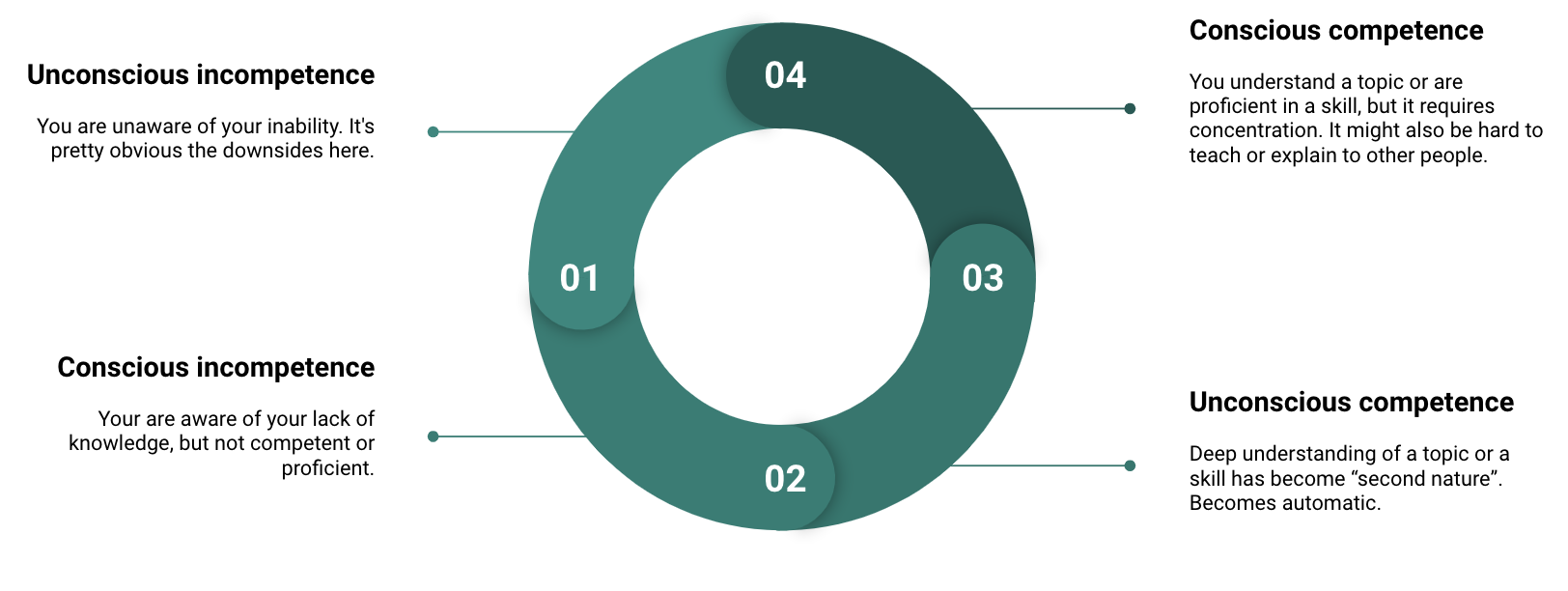

There’s another model which explains progression of knowledge. The four stages of knowledge:

Four stages of knowledge

Four stages of knowledge

While there might be some ignorant bliss that goes with unconscious incompetence, it’s ideal to be aware of what stage your knowledge or skill is at. Then progress as many as possible through the stages, especially from the first stage!

There’s still issues with model.

For anything non-trivial, conscious competence is not a singular final state. Our knowledge is always incomplete. It either contains errors or the world has moved on. What was once true, now might not be.

But we can use this knowledge to help us problem solve and make better decisions. Understanding what is most likely fact, what is probable, what is unlikely and then what is false.

Build our self awareness and confidence in what we know. But we should also be humble. Be aware that we might be wrong, and be aware there is always more to learn.